I begin today with a word of gratitude. I am grateful to Louise, your pastor and my pastor, for inviting me to offer this morning’s sermon. And I am grateful to you, the people of Central Presbyterian, whether you are in this sanctuary or joining virtually, for being open to having me as today’s preacher.

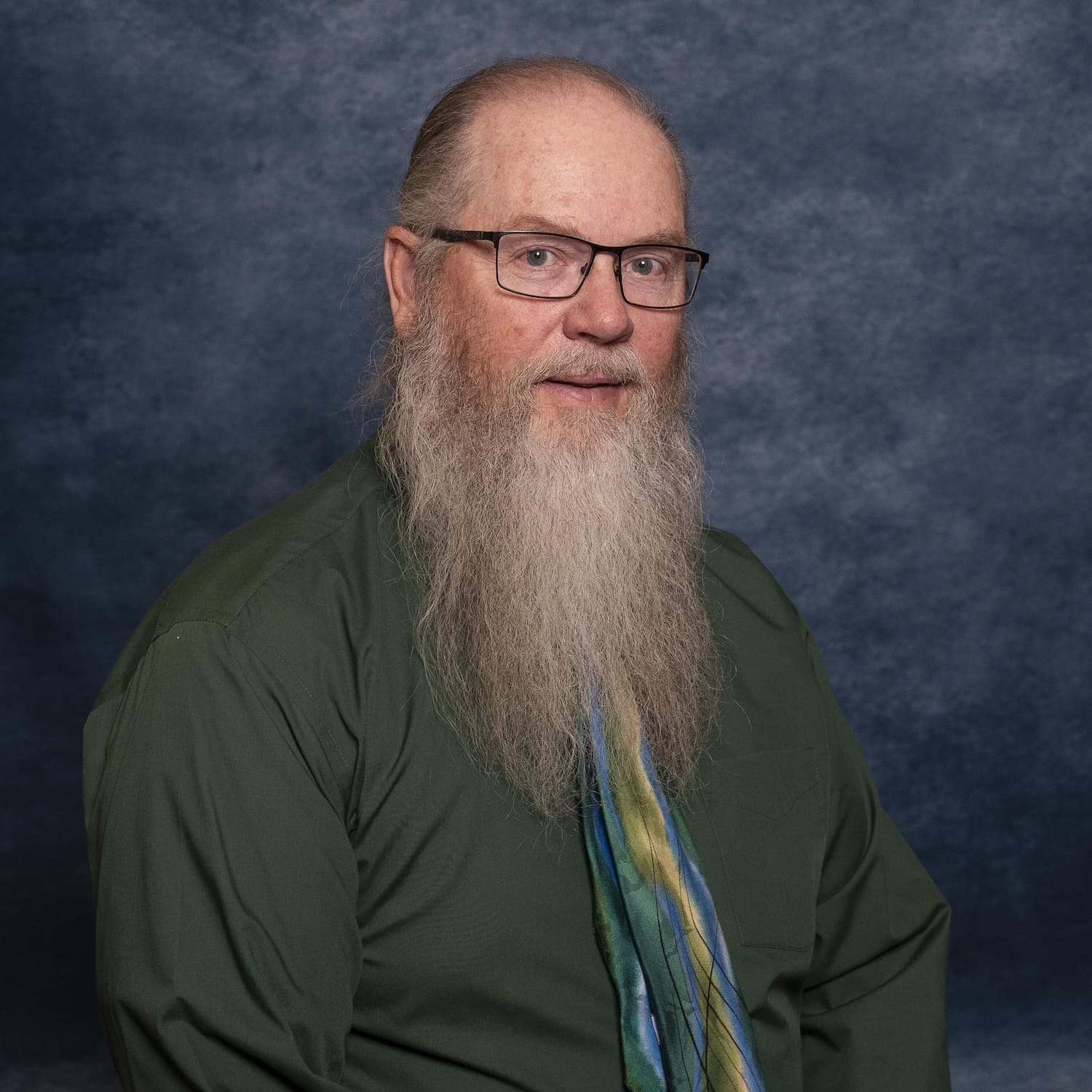

More importantly, I want to thank you for the ways you have welcomed, and continue to welcome, my husband and me. Ed and I started attending worship at Central somewhere around four years ago. Although I have not consulted with him on what I’m about to say next, I doubt Ed could disagree: From our first Sunday here, we felt your embrace. You managed to both greet us warmly and give us the space we needed to feel comfortable.

Since that first Sunday we’ve been able to form relationships of various types with many of you. You have accepted our gifts of service as Ed serves on a personnel search committee and I recently joined the Faith Formation Council. Some of you, both here in the sanctuary and almost certainly worshipping remotely, have even invited us into your homes where we have been able to laugh and share, getting to know one another and growing closer together.

Through your welcome, through your hospitality, you have continued to build the reality of “beloved community,” something Louise references regularly. I am deeply grateful for these gifts you have given us.

Since I have the honor of briefly occupying a Presbyterian pulpit, perhaps I should quickly offer my Presbyterian bona fides. To begin with, my brother recently had his DNA analyzed and, assuming our parents told us the truth about having the same mother and father, I was surprised to find out I’m almost 25% Scottish. So, I guess you could say Presbyterianism is in my blood.

I started attending First Presbyterian Church of Fort Collins with my family while in the second grade and remained through my early-adulthood. I attended Sunday School, sang in the children’s choir, and was a member of the youth bell choir. I was confirmed at 13, ordained as a Deacon at 16, and served as a Youth Advisory Delegate to the Synod of the Rocky Mountains. I attended Highlands Camp annually for many years, first as a camper and later as a counselor. It was at First Presbyterian Church of Fort Collins where I first discerned a call to the ordained ministry.

While I can’t be certain, I think it’s safe to say it was at this church where I first heard the Parable of the Prodigal, today’s scripture lesson. A reading from the fifteen chapter of Luke’s Gospel, verses 1-3, and 11b-32:

As many of you are aware, throughout this Lenten season the messages are inspired by scripture and informed by Amanda Gorman’s collection of poems, Call Us What We Cary. As Louise explained in a recent email to the Theology on Tap group, Amanda Gorman “believes our human identity is shape by the experiences, values, collective memory, trauma, and more – the stuff we hold on to, both good and bad, generative and destructive.”

When I first read these words in her email I thought: Wow Louise, that’s pretty deep. It also seems somewhat burdensome. The stuff we hold on to, both good and bad, generative and destructive, traumatic. While I believe Gorman’s concept is true, it’s also bothersome to think that I, that we, are everything we hold onto, including all of that stuff, all of that baggage. Without trying to take anything away from Gorman’s idea, I must admit it made me seek relief as I thought of R & B Artist Mary J. Blidge singing:

Bag lady you goin’ hurt your back

Draggin’ all ’em bags like that

[…]

One day all ’em bag goin’ get in your way

So, pack light, pack light

I couple this idea of Gorman’s poetry with the fact that we are in the Season of Lent, traditionally observed as a time of repentance. Despite the negative connotations many associate with the word ‘repent,’ in its original and simplest form it means simply to change course, to turn around, to come to new, healthier, more faithful ways of being and doing.

While Amanda Gorman describes who we are in her poetry, she also embarks on this Lenten journey of understanding who we can become, both as individuals and as a community. Lent is about acknowledging who we are while at the same time taking steps to move into a better, truer version of ourselves. If we are what we carry, then it seems to me that before we can even think about who we are becoming we have to take inventory of what we are holding onto, of what we are carrying around. In order to change, in order to grow, in order to become, we must change what we carry. I’d suggest we heed Mary J. Blidge’s words and pack light.

“… in order to grow, in order to become, we must change what we carry.”

The parable that is today’s lesson is about two kinds of relationships. The first is about our inter-personal relationships. As I look at the relationship between the father and the two sons, it seems to me one of the first things we might want to stop carrying, one of the things we need to lay aside, is our expectation of others, because these expectations often get in the way of our relationships.

Early in our dating relationship, before we had any serous disagreement, one night Ed asked me what I thought would happen when we had our first major argument. He seemed a little surprised when I told him, “I know exactly what will happen.” See, I had an expectation. So, I went on to explain how the day after the argument he would call me to say he was sorry, admit it was all his fault, apologize profusely, send me flowers, and assure me it would never happen again. Imagine my surprise when we did have our first big argument and things didn’t work out quite as I had envisioned.

When we watch the plot surrounding the father and his two sons, we see relationships that are broken, relationships that are restored, and relationships that remain horribly strained. The elder of the two sons is in a strained relationship with both his father and his brother because neither of them acted in the way he expected, the way he wanted. His younger brother turned his back on his family and his culture. The father welcomed the younger one back freely and joyously with no rejection, no repercussions, no consequences for his previous behavior. Neither the younger’s breech nor the father’s quick restoration of the breech fit the scripts that were acceptable to the elder.

Taking the elder brother’s side for a moment, there is every reason for everyone in this story, including the original hearers of the parable, to reject the younger son. He turned his back on his father, his family, his community, and his faith as he set out on a self-absorbed, and ultimately self-destructive, journey of self-fulfillment. Yet Jesus’ lesson is not one of separation and alienation but of bringing him back into the fold, of laying aside anger, laying aside resentment, laying aside a desire for retributive justice, so we have room in our arms to pick up things like welcome, forgiveness, and restorative justice. I don’t know about you, but for me the latter load seems lighter to carry.

The other type of relationship Jesus is talking about in this story is our communal relationships. More specifically, it’s about who is worthy to belong to and who should be banned from community.

Today’s lesson starts not with the parable itself but with the reason for the parable. In verses 1-3 we are told Jesus was in community, beloved community, and that community included tax collectors and sinners. The scribes and the Pharisees questioned the validity of this community because it was filled with undesirables, with people who didn’t conform to institutional rules or cultural expectations.

I told you how my relationship with the First Presbyterian Church of Fort Collins began, but I haven’t yet shared how it came to an end. I was in my early twenties and was coming into my own as a self-accepting gay man. At the same time, the Presbyterian Church (USA) was struggling with the place of sexual minorities, specifically gay men and lesbian women, in their ranks. The official position of the church at that time became that while gay and lesbian people could be members, they were unsuited for ordination as Deacons, Elders, or Clergy. Some individual churches went even further and fired non-ordained staff who were in same-gender relationships.

While nobody came up to me directly and told me I was no longer welcome to fully participate in the life of the church, the official position of the PCUSA along with a couple of other factors made it clear to me that I was not welcome. I reasoned: If I’m not welcome here, then why am I hanging around here? So, I left, and I set off on a different journey, and beloved community diminished because of our estrangement.

As an aside – but an important aside – this is how I know that even introducing anti-LGBTQ legislation like the ‘Don’t Say Gay’ bill in Florida, the anti-Trans initiatives coming out of Texas, and a host of other legislation throughout the country, are dangerous and destructive. Whether or not they become law, whether or not they are enforced, they clearly say to some of the most vulnerable of our children – those who have a higher incidence than their peers of being bullied, of struggling with chemical dependency, of suffering with mental health issues, of experiencing homelessness, and of dying by suicide – that they are not welcome. Even if the politicians are not speaking directly to these kids, trust me when I tell you, this message of unwelcome is loudly and clearly received, far too often with literally deadly consequences.

In articulating the concept of beloved community Dr. King shared his belief, and I’m quoting from The King Center website here, “Racism and all forms of discrimination, bigotry and prejudice will be replaced by an all-inclusive spirit of sisterhood and brotherhood.” We know that judging people by the color of their skin is wrong; we know judging people by who they love is wrong; I hope we know that judging people by how they identify and present themselves as gendered beings is wrong. All these things hamper community. But I suggest to you, especially in today’s world, these prejudices often extend into pre-judging people based on whether they are Republicans or Democrats, MAGA supporters or never-Trumpers, liberals or moderates. Who among us is not guilty of making assumptions about others based on their education, perceived socio-economic status, speech patterns, stance on masks and vaccines, or even whether they root for the Broncos or the Raiders, the Rockies or the Dodgers. Racism, discrimination, bigotry, prejudice and pre-judgments of all sorts; this is just some of the baggage we carry, both individually and collectively, some of the baggage we need to lay aside in our continuing quest for beloved community.

When I left the Presbyterian church I didn’t just drift away. I left intentionally and officially by sending a letter to the Clerk of Session resigning my ordination as Deacon and my membership in the church. In what is either an act of predestination or a twist of fate (you pick), the Clerk of Session at that time was one of my grade-school Sunday School teachers. So, I wrote and told one of the people who was an important part of my time growing up in this church home why I was leaving home. A month or so later I received an official letter back, signed by both the Moderator and Clerk, stating that the Session received and acknowledged my resignation. Also inside the envelope containing the official notice was a hand-written note by the Clerk, by my Sunday School teacher. I don’t remember exactly what it said, but I do remember she told me that regardless of how others felt, as far as she was concerned I would always be welcomed, always be accepted, always be loved. It was a beautiful gift of grace, and I had to lay aside a bit of my hurt and disappointment so I had room in my arms to accept this gift and carry it with me.

Toward the end of the Parable of the Prodigal, Jesus answers the objections of the scribes and Pharisees by offering a picture of beloved community: a lavish party filled with feasting, and music, and dancing. At this party, absolutely everyone is welcome – even, especially, the wayward son.

Although everyone is welcome, not everyone is in attendance. The party is going on inside while father and older son are outside, the parent begging his child to come in and join the festivities, be part of the community. At least for now, the son is holding on too tightly to too much to go through those doors and join the celebration. In doing so he is not only rejecting his brother, he is blocking his own participation in beloved community.

Interestingly, this parable ends without resolution. We have no idea whether or not the child heeds his parent’s entreaty. Likewise, this message must end without resolution. The concluding lines are up to you. Look at what you are carrying. What in your arms might be getting in the way of relationship, of community? Will you hold fast and let it continue to be a growing burden? Or are you willing to at least try to lay it aside? I hope you choose to pack light.